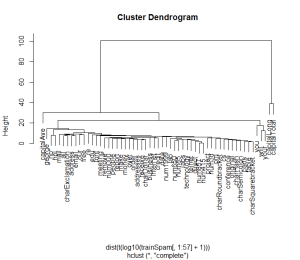

Contents cited from Coursera class Data Analysis from Johns Hopkins University by Jeff Leek. The dataset that Jeff was working with comes from the package kernlab (kernal based machine learning lab).

library(kernlab); data(spam); set.seed(3435);

trainIndicator = rbinom(4601, size=1, prob=0.5)

table(trainIndicator)

0 1

2314 2287

# table command here is called: Cross Tabulation and Table Creation which comes very handy

1. Look at the training set with the commands: names(data), head(data), table(data$col)

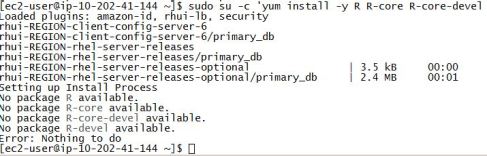

2. Plot

plot(log10(trainSpam$capitalAve+1) ~ trainSpam$type)

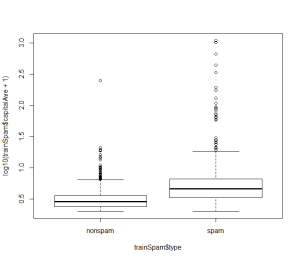

# you can also use pairs command here

plot(log10(trainSpam[,1:4]+1))

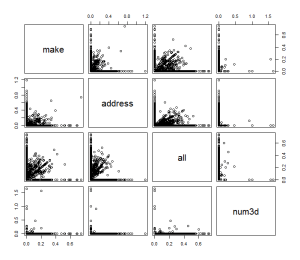

plot(hclust(dist(t(log10(trainSpam[, 1:57]+1)))))

# the code below demonstrate a basic process for statistical prediction/modeling

trainSpam$numType <- as.numeric(trainSpam$type) – 1

costFunction <- function(x,y) {sum(x!=(y>0.5))}

cvError = rep(NA, 55)

library(boot)

for(i in 1:55){

lmFormula = as.formula(paste(“numType~”, names(trainSpam)[i], sep=””))

glmFit = glm(lmFormula, family=”binomial”, data=trainSpam)

cvError[i] <- cv.glm(trainSpam, glmFit, costFunction, 2)$delta[2]

}

# measure of uncertainty

predictionModel <- glm(numType ~ charDollar, family =”binomial”, data=trainSpam)

predictionTest <- predict(predictionModel, testSpam)

predictedSpam <- rep(“nonspam”, dim(testSpam)[1])

predictedSpam[predictionModel$fitted > 0.5] = “spam”

table(predictedSpam, testSpam$type)

– predictedSpam nonspam spam

– nonspam 1348 398

– spam 81 481

(We can see the spam classifier we built only using the dollar sign did a pretty good job for non spam emails but for spam emails, the output turned out to be half and half)

And the error rate is about 22%